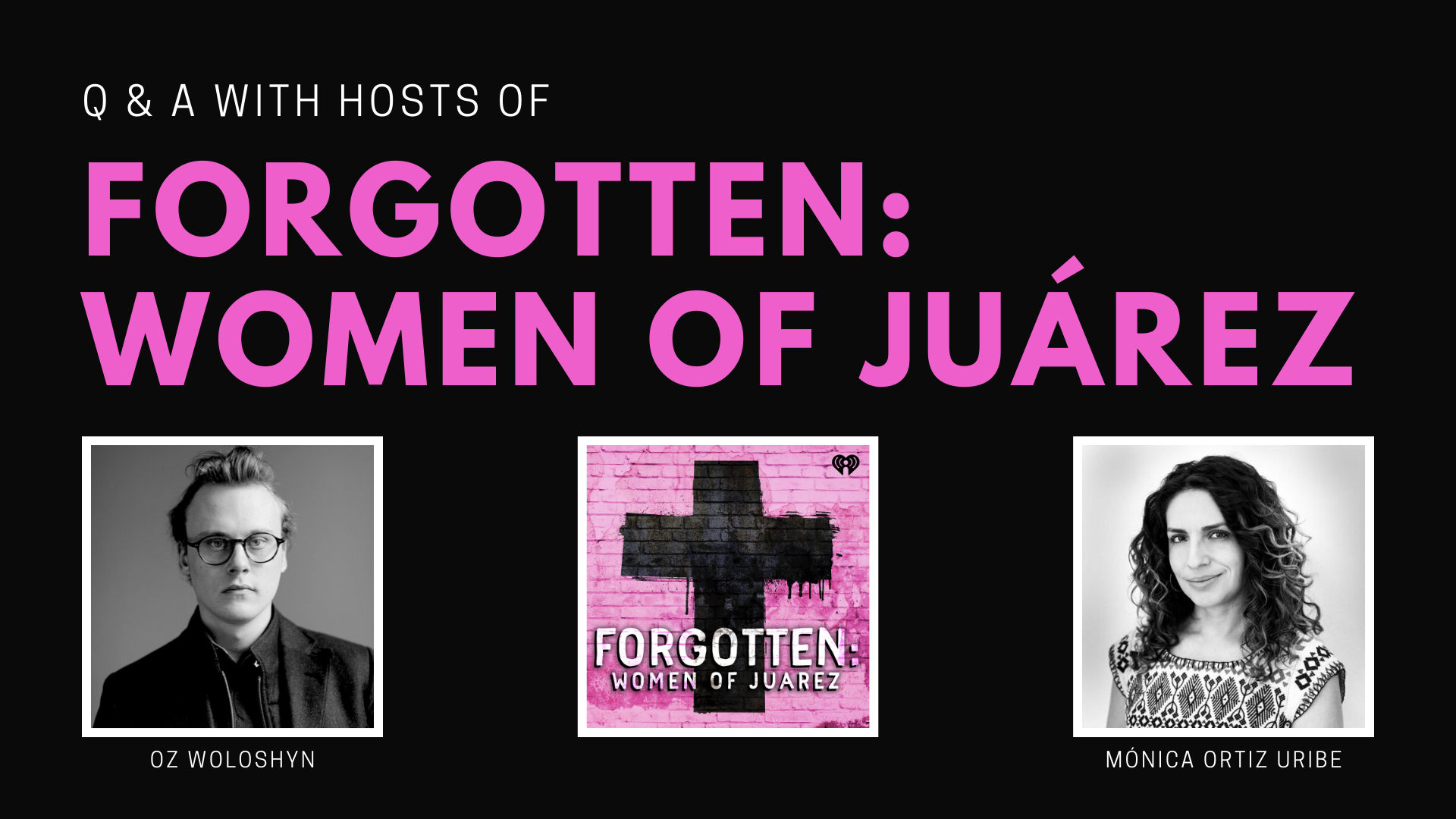

Q&A with hosts of Forgotten: Women of Juárez

by Mo’ Lanee Sibyl on July 17, 2020.

I have always been fascinated with the human mind, especially the great and dark lengths it can go. It might explain why watching true crime shows on TV still remains a favorite pastime for lazy Sunday afternoons. One of my favorite aspects of these shows is the ending: justice is served and the victims are offered closure.

But, that’s TV. Real life rarely follows that path. This is certainly true for the new podcast, Forgotten: Women of Juárez, by Oz Woloshyn and Mónica Ortiz Uribe. The podcast investigates the mysterious disappearance of women in Juárez, Mexico over the course of decades. Finding justice for these women proves to be incredibly difficult given a weak judicial system laden with corruption, a contentious border relationship with the US, and American consumerism.

As someone who’s been to Juárez several times (wrote about it here) and lived near its border, listening to this podcast was eye-opening for me as I had no prior knowledge of the femicides. Chatting with the hosts of the podcast provided more details on their mission to keep telling the stories of these women with the hope to finally bring the perpetrators to justice.

I have visited Juárez several times, having lived in Las Cruces, NM – a town bordering El-Paso, TX, and Juárez. So I guess it was only natural for me to want to listen to your podcast and follow the case closely. But in all the three years I maintained residency in Las Cruces and visited Juárez, I never heard about this case. Why do you think there’s low awareness of these killings, especially in America and international media?

Mónica: I am always surprised when people tell me they haven’t heard of the femicides in Juárez. There was a time when you couldn’t mention Juárez to an outsider without them asking, “Isn’t that where women are being killed?” Part of the reason is that these killings have been eclipsed by another tragedy in Juárez, a rampant and bloody drug war. Thousands of people, mostly young men, have been killed in Juárez since 2008. Drug-related violence has dominated the headlines in Juárez and increasingly throughout Mexico. There’s a new wave of drug violence sweeping the country at this very moment. But that doesn’t mean femicide has stopped. On the contrary, an uptick in drug violence is usually accompanied with an uptick in violence against women. The Mexican government has said that last year nationwide an average of ten women per day were killed in violent acts.

Oz: I had also made several trips to El Paso, working on another project, before I heard about the femicides in Juárez. When I first started asking people questions the response I received was: “not again, not another outsider coming in to try and tell this story”. Locally, I can imagine the emotional toll and the horror of the story make it hard to talk about, as well as the complicity that El Paso has in Juárez’s fate. Nationally, divisive political rhetoric about “us and them” has served to dehumanize the residents of Juárez and lower the level of empathy with their stories. In fact, one of the titles we considered for the podcast was “Girls Next Door.”

The podcast is so well done. The story is very compelling and the pain and suffering of the victims and families shine through every episode of the story. Thank you for giving all these the recognition it deserves. Curious to know why you started this podcast?

Mónica: To me this has always been the story that’s weighed heaviest on my conscience as reporter, as a woman, and as a Mexican American. I’m doing this podcast because I feel I owe it to the women who died. As the granddaughter of Mexican immigrants who grew up in El Paso, I had opportunities they didn’t. It’s wrong that their lives were stolen in this most horrific way. It’s important not only for people to understand how they died, but why. So many of these women were kind-hearted, hard-working, vibrant human beings. Their stories deserve to be told.

Oz: My grandfather was a refugee to Britain after the Second World War and I’m an immigrant to the U.S., so I’ve always been drawn to understanding more about borders and how they can influence a person’s fate. I had never come across a story that more obviously highlighted the power of a border than the unsolved murders of hundreds of women less than a mile from one of America’s safer cities. The cruel irony was made all the more resonant to me because so many of the victims worked in American-owned factories, making goods for U.S. consumers, from medical gloves to seat belts.

Given the fact that this case is still developing, has spanned almost three decades, and has encountered significant obstacles in terms of systemic and governmental inefficiencies, what concerns (if any) do you have about your safety and those of everyone involved in this project?

Mónica: Fellow journalists, activists, family members, and investigators have been threatened for their work with respect to the Juárez femicides. A couple of attorneys were assassinated for defending two scapegoats that were pinned with the crimes. When it comes to this subject everyone must decide for themselves how far they are willing to go. Mexico is one of the deadliest countries for journalists. The Trump administration has been openly hostile to journalists. Yet journalists have made important revelations about who and what is behind the femicides in Juárez and elsewhere in Mexico. That kind of information can help the public be more vigilant. Ideally it should also pressure authorities to take action, but that is less often the case in Mexico and to a certain extent in the U.S.

Oz: I have been completely humbled working alongside Mónica by the courage that she brings to her reporting. And as I met other journalists from the border, people like Diana Washington Valdez and Alfredo Corchado, I understand the risks of reporting this story more and more clearly. Angela Kocherga told us about her reporting on the drug war in Juárez, saying: “I remember stepping in blood, and my shoes being soaked, and having to throw them away at the end of the day.” But these are not reporters who signed up to be conflict journalists, they are reporting on a city that is less than a mile from their home, and which is almost as much part of their identity as El Paso.

As I listened to the podcast, I experienced a great deal of frustration regarding how the Mexican government and press, as a whole, have handled this case. Corruption aside, there’s also the lack of infrastructure. For example, having no comparative database to run the semen sample found in the one victim. Then there were instances of failure by authorities to act on evidence or produce convictions. What has been the most frustrating part of this story for you?

Mónica: The impunity, seeing the same cycles of injustices repeat themselves, and of course seeing more women killed and more families confront a lifetime of grief.

Oz: As the podcast unfolds, it becomes clear that officials on the U.S. side of the border are not immune from corruption themselves. The border wall is imposing but it does nothing to stop the power of the cartel’s money. The premise of most true crime podcasts is that justice is within reach, if only the truth can come to light. In the case of Forgotten, that’s less clear.

Why do you think the murders have not been solved? What are some theories on individuals or groups committing them?

Mónica: The true killers have never been brought to justice. These murders were not solved because in some cases the police were implicit in the crimes. There are lots of explanations for what was happening to these women. In some of the most high-profile cases it’s believed they were taken as trophies by drug cartel members. Some were taken as part of a sex-trafficking ring. Others were victims of extreme domestic violence. Some were involved in the drug trade themselves.

Oz: President Trump famously cited the risk of “murderers, rapists and bad hombres” crossing into the United States from Mexico. Ironically, the FBI had serious concerns that one or more American serial killers were taking advantage of the environment of impunity and vulnerability in Juárez to commit murders across the border in Mexico, before returning home to the U.S. In one horrific case, a man murdered a woman in Ruidoso, NM and drove to Juárez to dump the body, hoping it would get lost in the volume of unsolved murders of women there.

How do you see this case ending? And what are your plans for the future of this and other podcast(s)?

Mónica: I would like this podcast to end with Americans recognizing that these women’s murders are not simply Mexico’s problem. I hope we can help Americans understand how our consumer demands fuel violence and create a huge community of vulnerable people in places like Mexico. I also hope we can produce this podcast in Spanish for the benefit of a Mexican audience.

Oz: In 1998, an American journalist called Chuck Bowden wrote a book called “Juárez: The Laboratory of Our Future.” He wrote about the murders of women and cited a toxic cocktail of uncontrolled neoliberal economic policies, corrupt authorities, and weakened institutions as drivers of violence. Bowden’s warning is more resonant now than ever before and I hope that we figure out how to heed it.

Final question: we ask all of our guests this question. Podcast Brunch Club is a community of avid podcast listeners. Outside of your own podcast, what other podcast(s) would you recommend?

Mónica: I have to admit I don’t listen to too many podcasts. I listen to and read the news mostly. My co-host did an excellent podcast called Sleepwalkers last year. It’s about the impact of artificial intelligence in our lives. Some of those impacts are frightening and I’m glad that podcast has made me aware of them.

Oz: There is an excellent season of CBC’s Uncover podcast called “The Village.” It details the serial murder of a series of men, many immigrants, in Toronto’s Gay Village, and how prejudice played a role in hampering the investigations.

About the author:

About the author:Mo’ Lanee Sibyl, B. Pharm, PhD is the chapter leader of the PBC chapter in Oklahoma City and the host and producer of The More Sibyl Podcast. She is a Nigerian-born, US-educated, Korean-speaking intellectual.

Hello

I was appalled and horrified by this report. I think it would be very helpful if you would at least name the parent company’s I am sure the American would call or write possibly boycott the companies the these woman worked at I was left very u satisfied with the ending on the podcast not really naming any responsible parities or companies. Americans can definitely do something if we know where to start it all about the money!

A couple observations:

1) I almost turned it off at the very beginning when Ms Uribe was sniggering about almost not wanting to collaborate with Mr. Oloshyn because “he was just another gringo”.

Just another gringo? Excuse me? How racist is that comment?

Apparently Ms Uribe believe’s that we’re all the same, and safe to dismiss .

2) There’s a strange amount of naivete bundled in this tragic tale. I lived in New Mexico half my life and in Cuidad Chihuahua for a year in the early 90s (yes, as a “gringo” or maybe “Gabacho” to Ms Uribe).

Mexico is famously corrupt and has been for decades. Nothing has changed, other than the cartels have bought more influence. When I heard the narrator talk about one of the characters going to the Federales for help, I almost laughed. One would actually believe the *Federales* would help track down corruption? Good grief, even we dumb Gabachos would know that that is a fools errand. I’m surprised they didn’t burst into laughter.

This is an important story that deserves better than this wide – eyed narration.

Mexico is full of good people that are governed and policed by one of the most corrupt governments on planet earth.

Mexicans are the only ones that can fix this.

While I found the podcast to be a combination of both pros and cons, I applaud the passion and effort that went into its production. A few points related to the Juarez killings which bear special mention:

-A 14 year old female survived an attempted killing in Juarez in the 1990s; she was brutally raped, assaulted, and left for dead. Her testimony led to the arrest of Jesus Manuel Guardado, a bus driver who worked for the Motores Electricos company where the girl worked as an assembler. Guardado was arrested and implicated five other bus drivers in the Juarez rape-murder ring. Eventually ten suspects were tried and convicted: Further info: https://www.myplainview.com/news/article/Ten-members-of-two-criminal-gangs-sentenced-for-8627923.php

-In 2003 reporter Cecilia Balli, who fit the physical profile of some of the victims, had a chance encounter with a male street vendor in Juarez who asked her if she was looking for work, and persistently attempted to interact with her. Balli, alarmed, declined; she believes this man may have had a connection to the killings. For further info: https://www.texasmonthly.com/articles/ciudad-de-la-muerte/

-“In 1996 a group of civilians searching for women’s remains in Lomas de Poleo came upon a wooden shack and inside it an eerie sight: red and white votive candles, female garments, traces of fresh blood, and a wooden panel with detailed sketches on it. On one side of the panel was a drawing of a scorpion—a symbol of the Juárez cartel—as well as depictions of three unclothed women with long hair and a fourth lying on the floor, eyes closed, looking sad. A handful of soldiers peered out from behind what looked like marijuana plants, and at the top there was an ace of spades. The other side showed similar sketches: two unclothed women with their legs spread, an ace of clubs, and a male figure that looked like a gang member in a trench coat and hat. The panel was handed over to Victoria Caraveo, a women’s activist, who turned it in to state authorities. Though the incident was reported by the Mexican papers, today government officials refuse to acknowledge that the panel ever existed.” For further info: https://www.texasmonthly.com/articles/ciudad-de-la-muerte/